Julius Paul spent the years 1892-95 living in New York and Chicago, two of the five largest cities in the world at the time. His wife Brunis and infant daughter Helen, on the other hand, were residing in the tiny farming village of Miłaczew located near the western frontier of what is commonly referred to as “Congress Poland” or sometimes “Russian Poland”. The area was much more Julius’s home than it was Brunis’s. Julius’s mother had probably moved to the area north of Kleczew by 1856, and his father had done the same no later than 1857. Julius himself was born in 1867 just 5 miles to the east of Miłaczew and was living in the village at the time of his marriage to Brunis. Many Pauls, Ludmanns, and Krügers lived in nearby villages or in Miłaczew itself. Brunis, on the other hand, had only lived in the area for a few years with her mother, her only nearby relative. Three months after her marriage to Julius, Brunis’s mother died. Eight months after Julius left for America, Brunis’s father died in Konin. The three years of waiting for Julius to send for her and their little daughter may have felt very long indeed.

By early 1895 economic conditions had improved enough in America — or perhaps better to say had improved enough for Julius — to finally bring Brunis and Helen over. Like Julius, they would not travel alone. Accompanying them was a 16-year-old girl named Bertha Henkelmann. We don’t quite know who Bertha was. A ship manifest describes Julius as her brother-in-law. Yet she is no sister of Brunis and I have yet to find any half-sisters of Julius marrying a man named Henkelmann. One of his Aunt Wilhelmina’s sons married a Henkelmann, however, so perhaps Bertha is a more distant relative by marriage. Regardless, she probably joined the trip to help Brunis with the trials of the voyage.

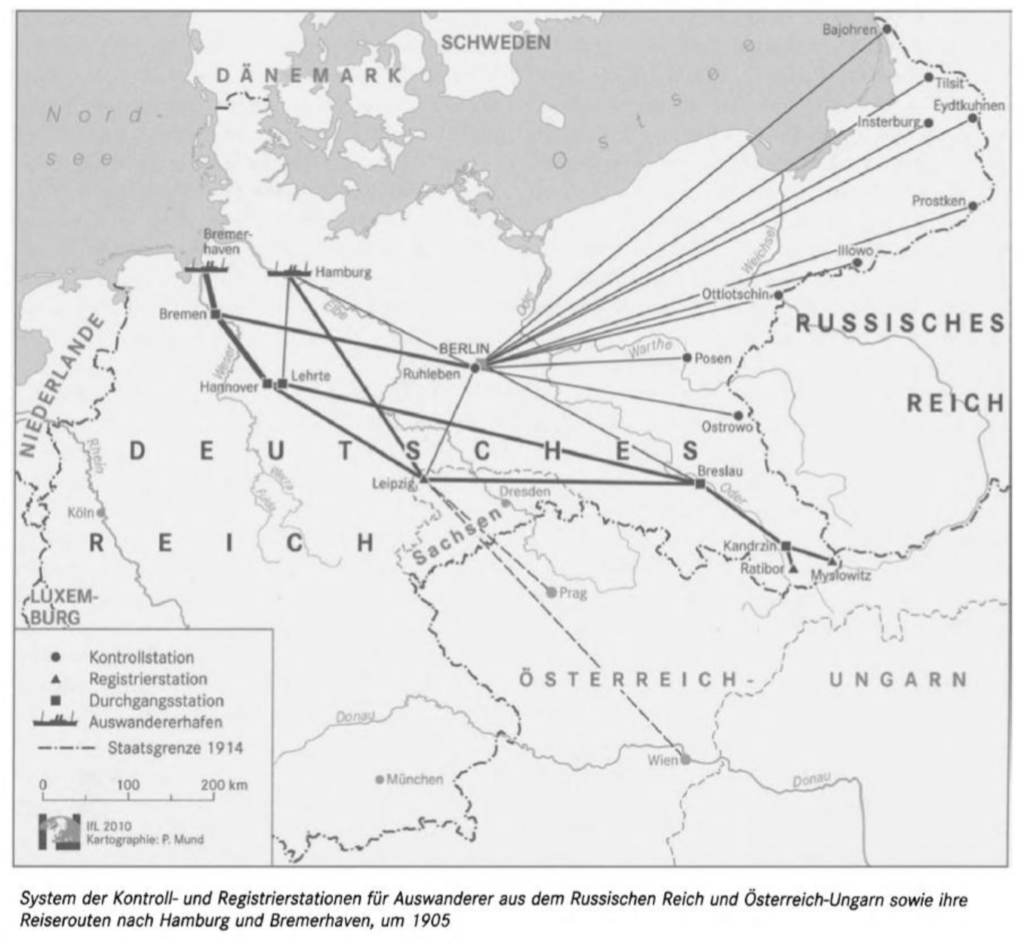

Like her husband before her, Brunis was heading for America via Hamburg. Some parts of the transmigration experience across Germany had changed since Julius left in 1892. In late 1894 the two great German shipping lines, Hamburg America Line (HAPAG) and North German Lloyd, began moving some of their immigration control operations from the Ruhleben station outside Berlin to a ring of smaller Kontrollstationen on the Prussian border with Russia and Austria-Hungary. Because of the strict US immigration controls imposed through the 1891 Immigration Act, the 1892 cholera outbreak in Hamburg brought to the city from Russia, and the generalized fear both in America and in Germany of migrants from Eastern Europe spreading disease as they travelled, all these stations expanded their responsibilities beyond simply checking migrants’ registrations and income. They now became mandatory bathing and disinfection centers as well. Control stations were becoming the key entry points into an increasingly sophisticated and efficient — and at times dehumanizing — system.

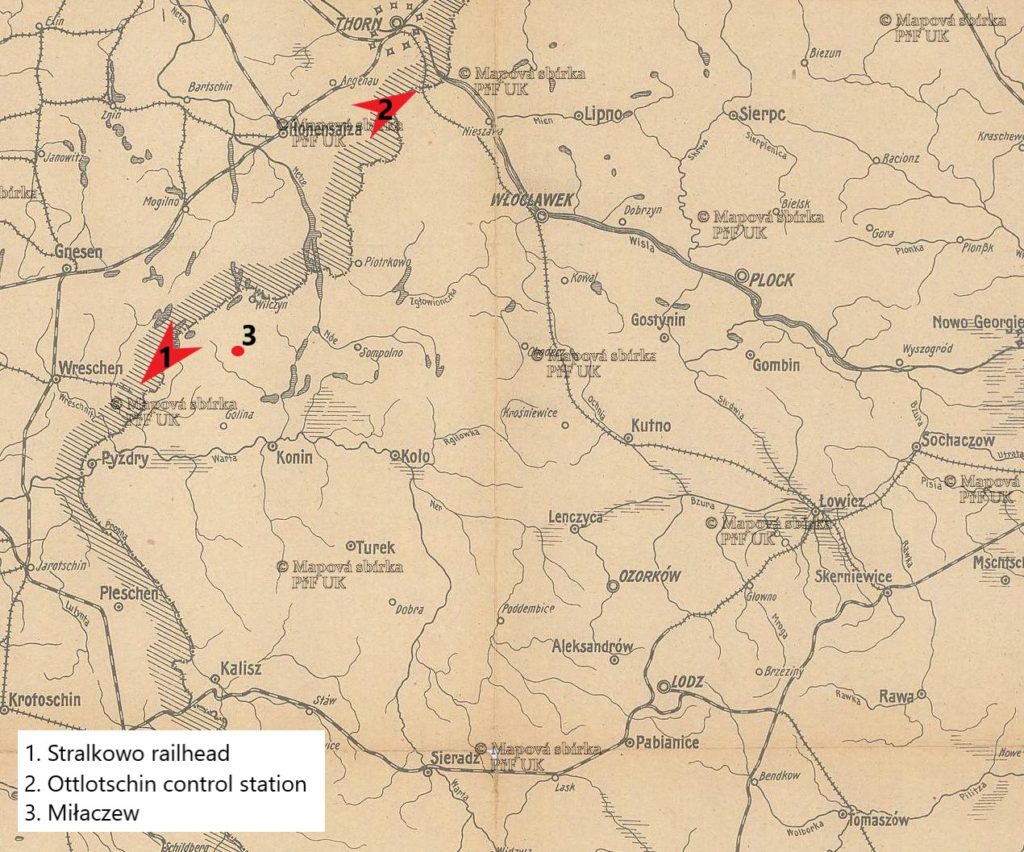

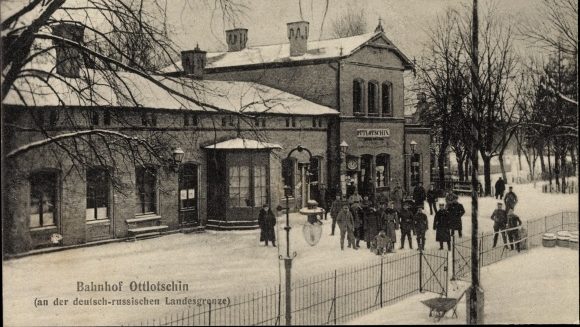

We don’t know if Brunis and Helen passed through one of these new control stations on the border. If they did, it probably would have been the nearest one at Ottlotschin (Pol.: Otłoczyn-Stacja), a grueling 90 mile journey by wagon or cart along backroads from Miłaczew. Perhaps a more likely trip would have been taking the highway eastwards 70 miles from Konin to Kutno and then the train westwards. Regardless of how they might have come to Ottlotschin, they would have then been forced to wait at the control station at least a day and perhaps longer for the designated migrant train to take them into Germany. As many migrants were still able to bypass the new control stations in their early years, it is possible that Brunis and Helen headed instead for Stralkowo (Pol.: Strzałkowo) and entered the German migration system at Ruhleben as Julius did.

That system largely treated its traffic the same way regardless of where it entered. The experience of Brunis and Helen was probably much like that of 11-year-old Mary Antin, a Jewish girl from Poland making the trek to America in 1894 with her mother and siblings. She describes riding in a fourth-class train car from the Kontrollstation at Eydtkuhnen (present-day Chernyshevskoye, Russia) to Ruhleben:

There were only four narrow benches in the whole car, and about twice as many people were already seated on these as they were probably supposed to accommodate. All other space, to the last inch, was crowded by passengers or their luggage. It was very hot and close and altogether uncomfortable, and still at every new station fresh passengers came crowding in, and actually made room, spare as it was, for themselves. It became so terrible that all glared madly at the conductor as he allowed more people to come into that prison, and trembled at the announcement of every station. I cannot see even now how the officers could allow such a thing; it was really dangerous.

Upon arrival at the major control station at Ruhleben, the migrants were subjected to the mandatory bathing and disinfecting regime:

In a great lonely field opposite a solitary wooden house within a large yard, our train pulled up at last, and a conductor commanded the passengers to make haste and get out. … our things were taken away, our friends separated from us; a man came to inspect us, as if to ascertain our full value; strange looking people driving us about like dumb animals, helpless and unresisting; children we could not see, crying in a way that suggested terrible things; ourselves driven into a little room where a great kettle was boiling on a little stove; our clothes taken off, our bodies rubbed with a slippery substance that might be any bad thing; a shower of warm water let down on us without warning; again driven to another little room where we sit, wrapped in woollen blankets till large, coarse bags are brought in, their contents turned out and we see only a cloud of steam, and hear the women’s orders to dress ourselves, quick, quick, or else we’ll miss—something we cannot hear. We are forced to pick out our clothes from among all the others, with the steam blinding us; we choke, cough, entreat the women to give us time; they persist, “Quick, quick, or you’ll miss the train!'”…

Assured by the word “train” we manage to dress ourselves after a fashion, and the man comes again to inspect us. All is right, and we are allowed to go into the yard to find our friends and our luggage. Both are difficult tasks, the second even harder. Imagine all the things of some hundreds of people making a journey like ours, being mostly unpacked and mixed together in one sad heap. It was disheartening, but done at last was the task of collecting our belongings, and we were marched into the big room again. … We were obliged to stand and await further orders, the few seats being occupied, and the great door barred and locked. We were in a prison, and again felt some doubts. Then a man came in and called the passengers’ names, and when they answered they were made to pay two marks each for the pleasant bath we had just been forced to take. Another half hour, and our train arrived. The door was opened, and we rushed out into the field, glad to get back even to the fourth class car.

For young Mary Antin, the trip onwards to Hamburg proved even more unpleasant than the one to Ruhleben:

If we had borne great discomforts on the night before, we were suffering now. I had thought anything worse impossible. Worse it was now. The car was even more crowded, and people gasped for breath. People sat in strangers’ laps, only glad of that. The floor was so thickly lined that the conductor could not pass, and the tickets were passed to him from hand to hand. To-night all were more worn out, and that did not mend their dispositions. They could not help falling asleep and colliding with someone’s nodding head, which called out angry mutterings and growls. Some fell off their seats and caused a great commotion by rolling over on the sleepers on the floor, and, in spite of my own sleepiness and weariness, I had many quiet laughs by myself as I watched the funny actions of the poor travellers.

SOURCES

Mary Antin, From Plotzk to Boston. W.B. Clarke & Co., 1899.

Tobias Brinkmann, “‘Travelling with Ballin’’: The impact of American immigration policies on Jewish transmigration within Central Europe, 1880–1914,” International Review of Social History 53 (2008).

Dan Diner, ed., Enzyklopädie jüdischer Geschichte und Kultur, Volume 1, 2011.

Pamela Susan Nadell, The Journey to America by Steam: The Jews of Eastern Europe in Transition. PhD Dissertation, The Ohio State University, 1982.

Klokan Technologies GmbH, Old Maps Online.

A map of the German migrant control system at its full development c1905. The control stations in Posen and Ostrowo did not yet exist when Brunis and Helen emigrated in 1895.

Western Poland in an 1870 map. I have marked the nearest rail connections to Miłaczew in 1895.

The control station at Ottlotschin (Pol.: Otłoczyn-Stacja) around 1914. Brunis and Helen may have crossed into Germany here in 1895.