The early years of marriage for Julius and Brunis Paul were marked by separation. The couple wed in January 1891. Their first child, Helen, was born in December 1891. And when little Helen was just three months old, Julius left his new family behind for America. They wouldn’t be reunited for three years.

Prior to the 1860s there was barely any emigration to speak of from Imperial Russia. Seasonal workers began leaving western parts of the Empire (especially Poland) for Prussia/Germany in that decade. Trickles of emigrants to North America turned into swells by the 1880s and a flood by the turn of the twentieth century. We don’t know exactly what motivated Julius to emigrate, but economic opportunity is the most likely reason. Perhaps ironically, very few Russians left the Russian Empire. Instead emigration was mostly made up of Jews, Poles, Balts and Germans. When Julius left in 1892, he was catching a wave of ethnic minorities turning their back on the tsarist empire and facing a new future in the west.

In the nineteenth century it was relatively easy for migrants from the Russian Empire to get in to burgeoning industrializing countries like Germany, Canada, and the United States. The hard part was getting out of Russia. The tsars had exercised an “attract and hold” population policy since the 1600s. In order to retain property-holders as well as a valuable labor force and tax base, any subject looking to leave the country – even for a short time – was legally required to secure a foreign passport (zagranpasport) and produce it to tsarist officials when crossing the border. Securing such a document not only demanded hefty fees at this time. It also required running a gauntlet of bureaucrats and paperwork that could take three months to complete (in comparison, Italian emigrants could get their passports in twenty-four hours). For poor laborers, these barriers made legal emigration more or less prohibitive. No wonder that around the time Julius left Poland, 50-90% of all emigrants from the Russian Empire departed the country illegally. We don’t know whether Julius ever got his passport, but considering his status as an orphan and a day-laborer, chances are he went with the majority and defied the law.

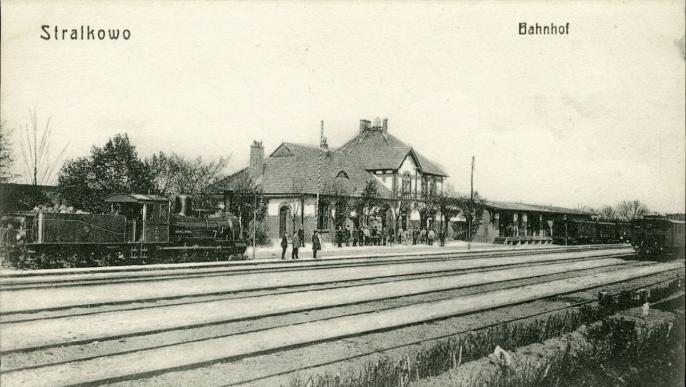

Between the Congress of Vienna (1815) and the beginning of First World War (1914), the border with Germany lay only ten miles from Julius’s and Brunis’s home in the village of Miłaczew. Whether crossing at an official border post by day or sneaking over the border by night, it is almost certain that Julius made his way for the German town of Stralkowo (Pol.: Strzałkowo) about fifteen miles away. There sat the nearest rail station, built in 1888 with a connecting line to Posen (Pol.: Poznań) and the world beyond.

SOURCES

Eric Lohr, Russian Citizenship (Harvard University Press, 2012), ch. 4.

“Strzałkowo,” Semaforek.

“Stacja kolejowa Strzałkowo,” fotopolska.eu.

The international border at Stralkowo (Pol.: Strzałkowo) in the early twentieth century. Julius Paul may have left the Russian Empire here.

The train station (Bahnhof) in the German town of Stralkowo (Pol.: Strzałkowo) in 1906. Julius Paul likely boarded a train here in 1892 at the start of his journey to America. This building is still standing today.

An excerpt from the famous Karte des Deutschen Reiches . This image is from 1893 and shows the pre-WWI border running between the towns of Stralkowo (Pol.: Strzałkowo) in the German Empire and Slupzy (Pol.: Słupca) in the Russian Empire, and the rail line ending in Strzalkowo. Clicking HERE takes you to an enlargeable version of the surrounding region. You can see how close Miłaczew (spelled here “Milatschew” and located near the center of the map) was to the border (highlighted in pink near the left side of the map).