Like so many immigrants to America in search of a better life, Julius Paul came with little by way of marketable skills or formal education. In Poland he worked as a day-laborer and couldn’t even sign his own marriage record because he was illiterate. Julius reported to the 1940 US Census-taker that he had exactly zero years of schooling! This background made it difficult for him to find any kind of work apart from that of an unskilled laborer.

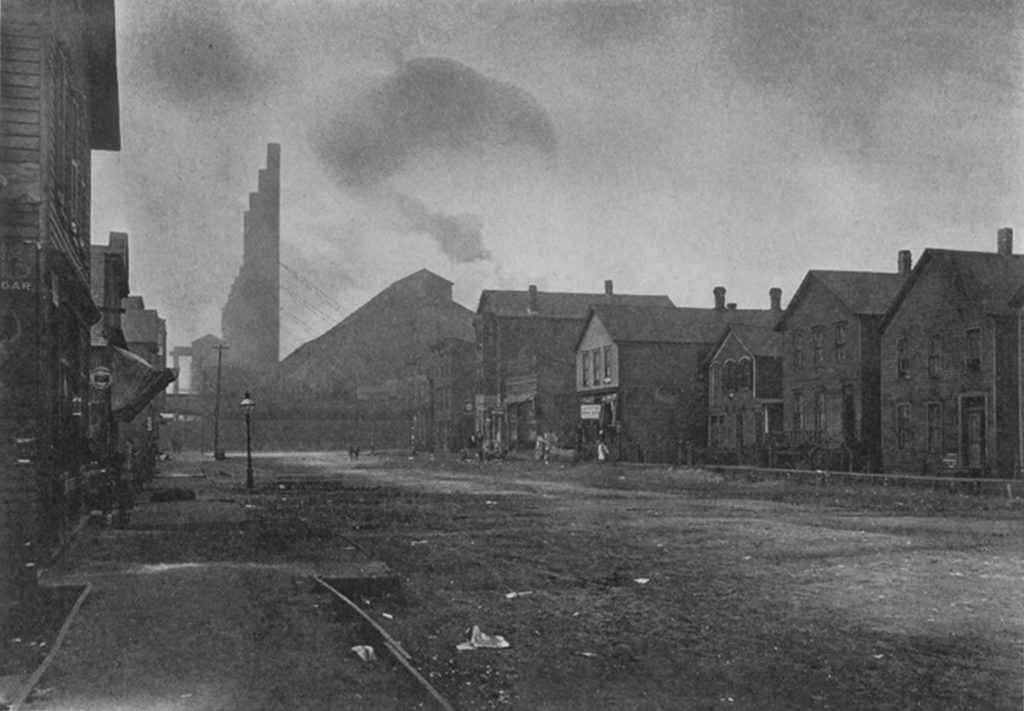

For all the years the Pauls lived in Chicago, Julius worked in the city’s steel mills. This explains why Julius and Brunis lived in the bleakest and most unsanitary neighborhoods. Their apartment on Bubbly Creek was located just across the river from the Union Steel and Union Rolling Mill plants (which in 1895 were part of Illinois Steel). Their homes in the Bush were located just blocks away from Illinois Steel’s vast South Works plant (after 1901, part of U.S. Steel). In the words of the Chicago School of Civics and Philanthropy’s 1911 report on the neighborhood, “Here a pall of heavy smoke darkens the sky by day, while by night the lurid glare from the furnaces tells of unceasing toil.”

Illinois Steel was truly a mammoth organization. The corporation was formed in 1889 through the merger of three Chicago and Milwaukee steel companies. Upon its creation it employed 10,000 people, making Illinois Steel at the time the largest corporation by employment in the world. The South Works was in turn the largest steel complex in Chicago. It sported the first integrated rail mill in the world, with iron ore entering by train at one end of the plant and finished steel rails exiting from the other. In Julius’s day the South Works covered about 75 acres of Lake Michigan shoreline south of 87th Street as well as extending along the north side of the Calumet River. Present-day South Lake Shore Drive (US Hwy. 41) was the actual shoreline then. Over the ensuing decades the South Works gobbled up some two dozen blocks of houses in the neighborhood and even expanded out into the lake atop giant slag heaps. While today Buffalo and Burley (then Superior) Avenues come to a dead end in the middle of the 8200 block, back in the 1890s the streets ran northwards all the way to 79th Street and Lake Michigan.

Working as a laborer in a steel mill was hard going. The heat was intense, the labor exhausting, and the working conditions grim. An 1894 McClure’s Magazine article on a Carnegie Steel plant in Pennsylvania gives a glimpse of life as an American steelworker in this era:

Everywhere in this enormous building were pits like the mouth of hell, and fierce ovens giving off a glare of heat, and burning wood and iron, giving off horrible stenches of gases. Thunder upon thunder, clang upon clang, glare upon glare! Torches flamed far up in the dark spaces above. Engines moved to and fro, and steam hissed and threatened. Everywhere were grimy men with sallow and lean faces. The work was of the inhuman sort that hardens and coarsens.

A plant like the South Works was both a steel plant and a bustling chaotic railyard. In Julius’s time around 130 miles of track wound around the sprawling network of the plant. Locomotives of every kind and size puffed their way about the grounds. Exhaust from the engines combined with that of the coking plant and the eleven blast furnaces made the South Works appear from a distance as “just an opaque mass of smoke, thirty million dollars’ [in 2021, ~$700m] worth of smoke”.

The work was not only hard and unhealthy. It was dangerous, too. At the South Works in 1906 there were 46 recorded fatalities. Serious injuries were never tallied in those days, but relying on figures from the German steel industry, it is likely that four times as many men (~180) that year were temporarily disabled (out of work >13 weeks) and eight times as many (~370) permanently so. Accident rates for immigrants at the South Works were generally twice as high as those for native English-speakers. Until major safety reforms began in take hold in the early 1910s, each year about 25% of immigrant steelworkers at the plant were killed or injured on the job. If you look carefully at the wonderful Paul family photo from c1917 that appears on the home page of this website, you will notice that Julius is missing much of his middle finger on his left hand. We don’t know how or where this happened, but it certainly could have occurred at the South Works. Injuries were in fact so routine that the company operated a hospital on site with 50 beds and a medical staff of seven. No wonder a famous 1907 magazine article about the plant was titled “Making steel and killing men”.

So was the working day long. Twelve-hour shifts were standard in American steel mills in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Julius probably alternated working the day shift some weeks, the night shift others. The day shift began at 6:00am and went through to 6:00pm. The night shift worked the opposite so that the mill could operate 24 hours a day. Amazingly enough, at the South Works, Sundays were 24-hour shifts which a steel-man worked every other week! Before the great merger in 1901 that created U.S. Steel, Illinois Steel’s main rival was Carnegie Steel, and Andrew Carnegie closed his mills but one day out of the entire year: the Fourth of July. There is little reason to think the South Works was any different. That being said, company owners were very responsive to market conditions, and if steel prices began to fall, an entire mill could be shut down for weeks at a time. According to the 1900 US Census, Julius spent four months of that year unemployed. This was no depression year, just the normal job insecurity of the American steelworker.

[Steel: Man’s Servant is an interesting promotional video from U.S. Steel showing a somewhat sanitized version of the steel-making process as it existed in 1938. Although this was forty years of technological and safety developments after Julius labored in the South Works plant, it can still give you some idea of how things must have been for him.]

SOURCES

Sophonisba P. Breckinridge and Edith Abbott, “Chicago housing conditions, V: South Chicago at the gates of the steel mills,” American Journal of Sociology 17 (2) (September 1911).

Willam Hard, “Making steel and killing men,” Everybody’s Magazine 17 (5) (November 1907).

Hamlin Garland, “Homestead and its perilous trades – impressions of a visit,” McClure’s Magazine 3 (1) (June 1894).

William T. Hogan, Economic History of the Iron and Steel Industry in the United States, Volume I (1971).

Looking north on Green Bay Street in the Bush at the South Works plant (1911).

Looking north on Green Bay Street in the Bush at the South Works plant (1911).

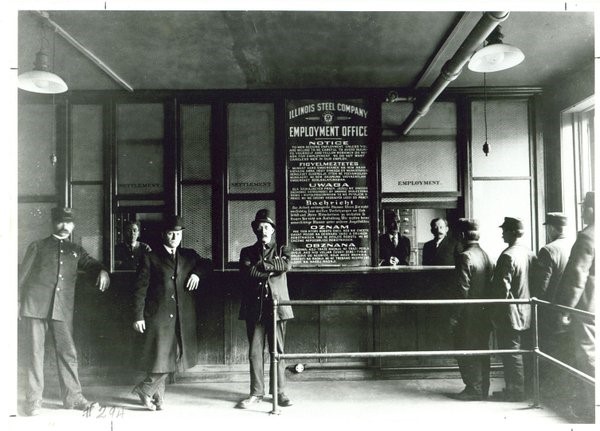

The Illinois Steel employment office in the years when Julius worked at the South Works plant. The notice board is written in six different languages — English, Hungarian, Polish, German, Slovak, and Croatian — reflecting the immigrant backgrounds of so many of the mill’s workers.

The Illinois Steel employment office in the years when Julius worked at the South Works plant. The notice board is written in six different languages — English, Hungarian, Polish, German, Slovak, and Croatian — reflecting the immigrant backgrounds of so many of the mill’s workers.

Steel Mill and Town. Smoke, ash, soot, fumes, dirt, molten iron, wooden sidewalks, dirt streets, densely packed housing (1939).