While Russian magistrates, police, and border guards were at least officially interested in proper documentation to leave the country, they could be and often were bribed to issue passports outside legal channels or allow migrants without proper papers to pass checkpoints. The German bureaucracy tended to be more scrupulous, efficient, and inflexible. As immigration from Eastern Europe increased, a great internal political tug-of-war began in Germany. On one side were people wary of huge numbers of poor unmoored migrants transiting the country on their way out of Europe, fearing crime and disease in particular. On the other side were shipping lines and port cities making huge profits off of transporting migrants across Germany and out to the wider world. The balance of power between these two factions resulted in the creation of a system of control stations and transit networks that efficiently funneled migrants from the German border to the German port cities of Hamburg and Bremen while keeping those migrants as removed from everyday German society as possible.

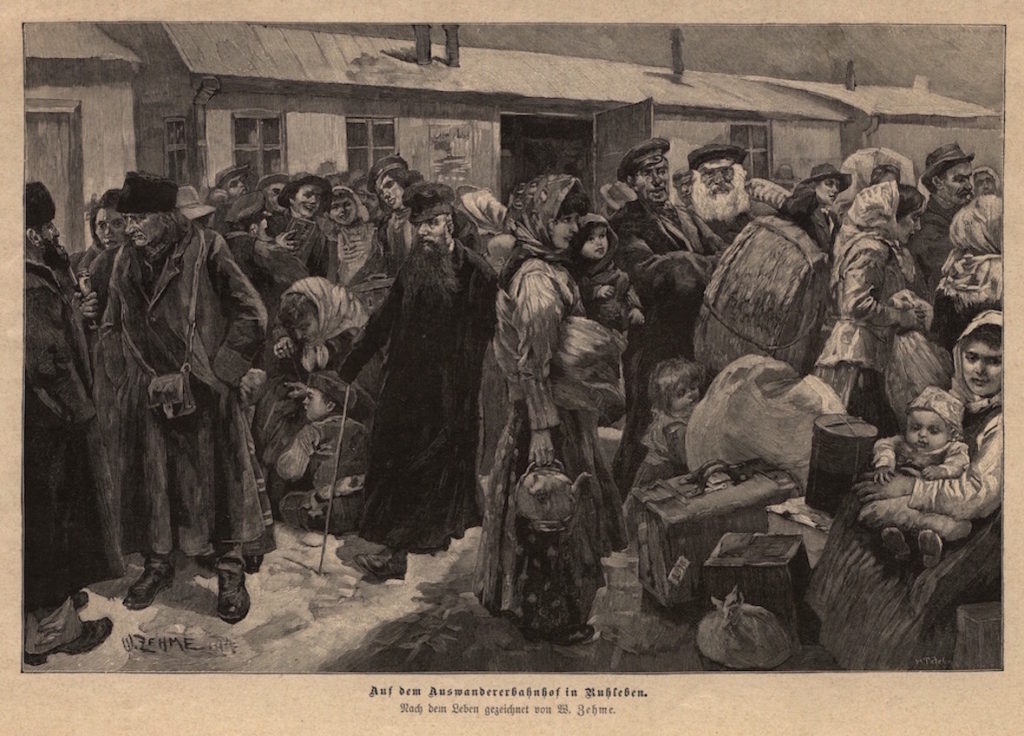

When Julius left Poland in the spring of 1892, this system was just getting established. Its first physical manifestations were the immigration control station (Auswandererbahnhof) at Ruhleben outside Berlin and the immigrant barracks constructed on the pier in Hamburg. Julius very likely passed through Ruhleben, a sort of scaled-down German Ellis Island. This train station was opened in November 1891. One of its purposes was to concentrate migrants outside the city and send them on dedicated trains straight to Hamburg and Bremen. Another was to inspect migrants and give the shipping companies confidence that their passengers would actually be admitted to their countries of destination. If a migrant was refused entrance in New York, Philadelphia, or Quebec City, the shipping company was required to return that migrant all the way back to Europe — usually on the company’s dime. Refusal at a port of entry was a legitimate fear. In March 1891 the United States passed its first comprehensive immigration legislation. This included the creation of a body of immigration inspectors at US ports and the construction of a new immigration control station on Ellis Island in New York Harbor. The law empowered those inspectors to turn away, among other categories of migrants, “paupers or persons likely to become a public charge” as well as “persons suffering from a loathsome or a dangerous contagious disease”. Thus in order to ensure their passengers could pass inspection on Ellis Island, the shipping lines made their passengers first pass inspection at Ruhleben.

While Julius likely passed through Ruhleben, he probably didn’t stay in the emigrant barracks in Hamburg. These were jointly financed and constructed by the Hamburg city government and the German passenger line Hamburg-America Line (Hamburg-Amerikanische Packetfahrt-Aktien-Gesellschaft, or HAPAG) and limited to use by HAPAG passengers alone. Julius had two tickets with much smaller UK-based shipping lines. The first was with the West Hartlepool Steam Navigation Company that would take him from Hamburg to the British port of West Hartlepool located along the north England coast. This was an indication of Julius’s poverty. About 20% of European migrants in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries took the indirect route through Britain rather than sail directly across the Atlantic. This option was cheaper because it was less regulated — meaning less comfortable, less clean, less safe — and often operated by smaller lines outside the international shipping cartel headed by HAPAG.

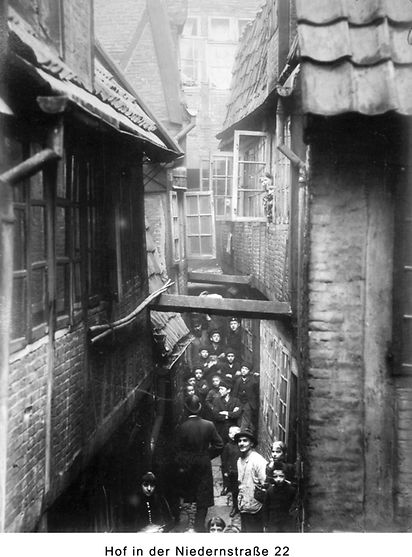

Unable to enter the new Hamburg barracks, Julius surely stayed instead in one of the city’s many lodging houses for emigrants prior to his departure. These were concentrated in the Alley Quarters section of the city, known for its very poor sanitary and safety conditions. Just four months after Julius was there, a cholera epidemic broke out in Hamburg that killed more than 8000 people before it was suppressed. The greatest level of mortality was precisely in the Alley Quarters. On an inspection of the district at the start of the outbreak in August 1892, physician, microbiologist and later Nobel Prize-winner Robert Koch observed “I have encountered nothing worse than the workers’ accommodation in the Alley Quarters, neither in the Jewish district in Prague nor in Italy. In no other city have I come across such unhealthy dwellings, such plague-spots, such breeding-places of infection. Gentlemen, I forget that I am in Europe.”

SOURCES

Richard J. Evans, Death in Hamburg (Clarendon Press, 1987).

Tobias Brinkmann, “‘Travelling with Ballin’: The impact of American immigration policies on Jewish transmigration within Central Europe, 1880-1914.” International Review of Social History 53 (2008).

“OBJEKT DES MONATS: ZEITUNGSGRAFIK, 1895,” German Emigration Center.

“Ein Stück vergessene Geschichte,” hamburg.de.